Regional libraries have produced a guide and a course plan, the Swedish Library Association has created a toolbox and the National Library of Sweden has done a survey.

All this is to support contingency planning for public libraries should their circumstances change. Priority is given to the dissemination of information and the library as a meeting place. Valuable lessons have already been learned.

“The flow of refugees and the pandemic taught us things we can build on,” Anna Persson, development officer at Library Development Blekinge Kronoberg, tells the Nordic Labour Journal.

Backed by the Library Act

The Swedish Library Act states that all 290 municipalities should have a library with access to all, a public library.

The act also states that the countries’ libraries have a democratic role and should “promote the development of a democratic society by playing a role in knowledge transfer and the free formation of opinions.”

The Library Act also serves as the basis for library plans formulated by and published by each municipality.

Swedish public libraries are identified as socially vital services in line with the national library strategy which the government presented in 2023. As a result, many public libraries are now preparing contingency plans for their operations.

No resistance

Newer library plans include paragraphs about the need to work with contingency plans while this is most often missing in older plans, explains Anna Persson.

“When the idea came up to discuss how to start writing such a plan, there was no resistance. More and more people realise that we must decide how to make decisions during a crisis.

“We wanted to support the heads of public libraries in the regions and organised a full-day session with them where we talked about this issue.”

During the day, a request emerged for support in writing contingency plans. The regional library services in Västra Götaland, Uppsala, Västmanland, Jönköping and Halland were contacted to set up a joint effort.

The resulting course took into account the different roles that the libraries play, with focus on communication, library space, media and information literacy, as well as priority groups – defined by the Library Act as being:

- Children and young people

- People with disabilities

- National minorities

- People with a mother tongue other than Swedish

The course plan included five digital sessions with a lecture followed by a discussion.

“We want the course plan to help staff start thinking about what happens to their operation in times of crisis or, in a worst-case scenario, war. After that, each municipality can write their own contingency plan,” says Anna Persson.

A lot of the material was collected from Digiteket, a platform offering continuing education and inspiration aimed at public library staff.

The course resulted in a guide to support the writing of contingency plans, serving as a complement to the toolbox created by the Swedish Library Association, which you can read more about later in this article.

More regional libraries have now expressed an interest in using the course structure.

Expert network with toolbox

Linda Wagenius did not have any doubts when in 2024 she was asked to join the board for the Swedish Library Association’s expert network on libraries’ role in total defence.

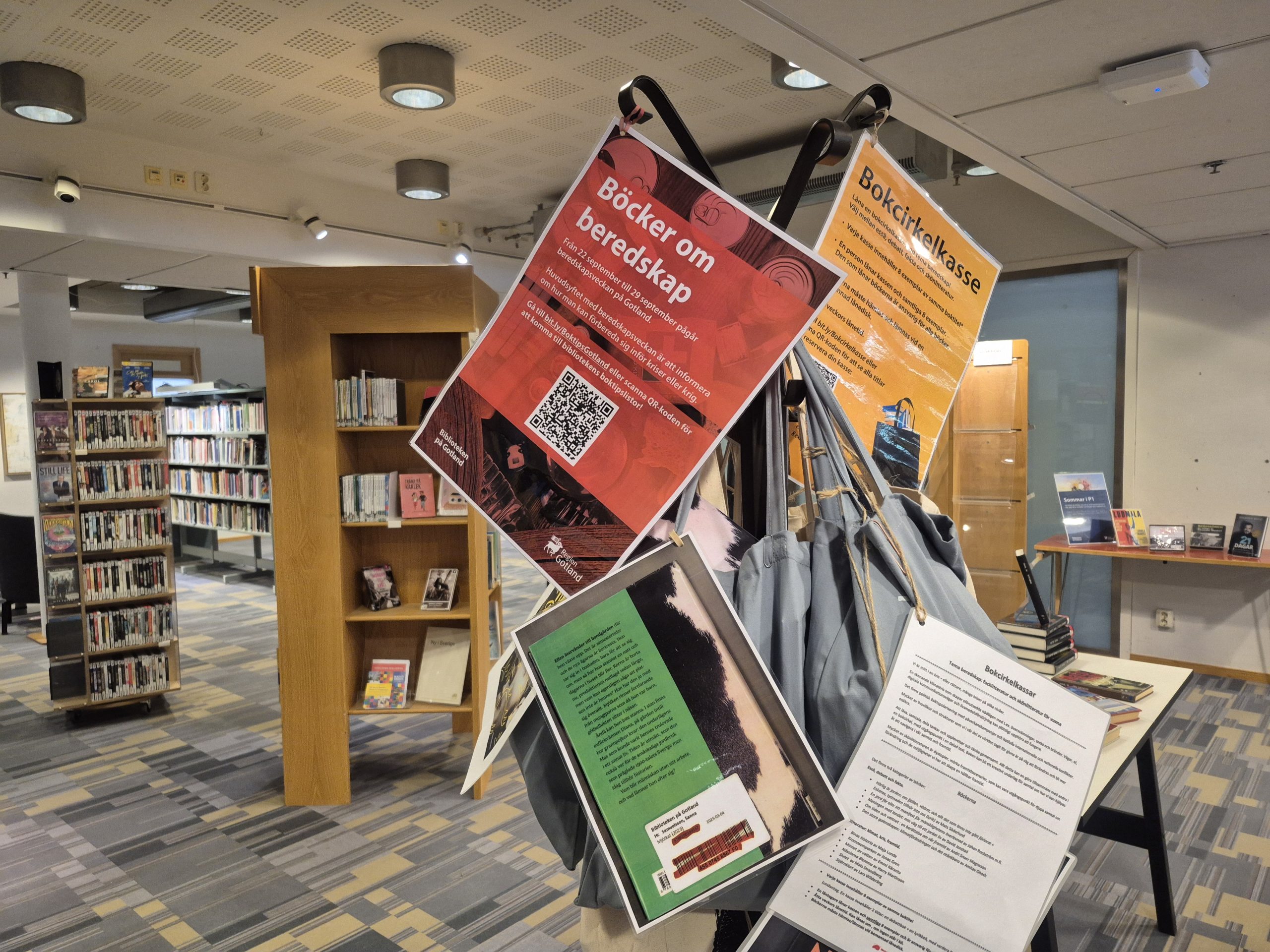

Wagenius is a librarian at the regional library of Gotland, and like Anna Person, she is also a library development officer.

“Gotland’s location in the middle of the Baltic Sea means that, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we had military patrols both at the airport and in the harbour. We also received many Ukrainian refugees.

“All this led to us starting to work on our own contingency. So saying yes to the expert network was easy. I was already engaged,” she tells the Nordic Labour Journal on the telephone from Sweden’s largest island.

As a board member, Linda Wagenius and library staff from various libraries have developed the Toolbox for Libraries’ Contingency Work.

The toolbox is meant to “summarise and concretise what libraries’ role in total defence can actually involve. It is based on the public’s need for information, which is important not least in times of crisis, and links this to the libraries’ information mandate,” writes the Library Association.

The toolbox includes

- A mapping of the public’s information needs during crisis or heightened preparedness

- An overview of how these are linked to the libraries’ missions and activities

- A methodological framework for local work, available as a download

- A stakeholder map

“The toolbox needs updating, and we plan to do this in the autumn. That is also when the Expert Network will organise a physical meeting for all the Library Association’s members. We will spend two days focusing on mental preparedness,” says Linea Wagenius.

The Expert Network will also participate in the media and information literacy course organised by the Swedish Media Authority in collaboration with public libraries, following a decision by the government.

A few days before the Nordic Labour Journal did the interview with Linda Wagenius, she had visited Norway in a professional capacity for the second time.

“Norwegians are familiar with the Swedish library strategy and the fact that public libraries have been included in several municipalities’ crisis management groups. So they are interested in how we think and work in Sweden,” she says.

Her first trip to her neighbouring country took her to a literature festival in Lillehammer, where she participated in a panel debate together with Lillehammer’s municipal director and the county governor of Innlandet County, among others.

Linda Wagenius’ second visit was to a cultural policy festival in Drammen, near Oslo, where she debated with other local politicians and Norwegian MPs. Both events also featured representatives from the library sector.

On the agenda

The role of libraries in total defence was first introduced in 2019 in the proposed national library strategy.

“That surprised some people. Since then, the issue has been on the agenda and has been reinforced by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine,” Oskar Laurin, head of library collaboration at the National Library of Sweden (KB), tells the Nordic Labour Journal.

The survey conducted by KB in 2023 on libraries’ preparedness efforts focused on municipalities that were in the early stages of their work.

“Preparedness is a key issue that needs to be refined. What do you prioritise in times of crisis or war? That is what we need to discuss,” says Oskar Laurin.

“Preparedness work requires resources, but resources allocated to public libraries have been cut while the number and complexity of tasks assigned have increased due to digitalisation. And with that, the need for more media and information literacy among staff.”

KB has not got a specific mandate from the government to work on public libraries’ preparedness, it is the current team under Oskar Laurin that is monitoring the issue.

“We have prioritised preparedness because it is topical. We are continuously looking at what needs to be better understood and developed across society. Recently, we have conducted a survey on academic libraries and preparedness.”

KB has no clear next steps for libraries and their preparedness, but the issue will be kept on the agenda.

“It might involve updating our information material, but we also need to work more with KB’s own preparedness,” says Oskar Laurin.