The refugee crisis has seen 800,000 people applying for asylum in an

OECD country in 2014, 600,000 of them in Europe. It has deservedly

gained massive attention. Yet the number still does not match the

number of migrants arriving through legal channels, outside of the

asylum system. For 2014 that number was 4.3 million people, up six

percent compared to 2013.

This is according to the OECD’s 2015 International Migration

Outlook, which has a separate chapter on health care professionals.

Most of the doctors seeking work in industrialised countries come from

India, while the Philippines is the world’s largest exporter of

nurses.

The Nordic countries have between 3.3 and 3.9 doctors per one

thousand people. The number of nurses varies between 11.1 to 15.4 per

one thousand people.

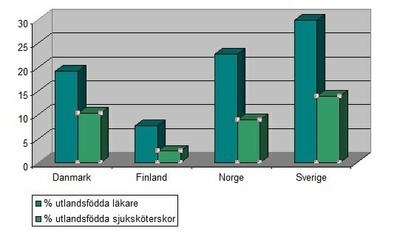

If you compare the proportion of foreign born doctors and nurses in

the Nordic region, you will find major differences. Finland has the

lowest number of foreign born doctors at 7.7 percent, and only 2.4 of

nurses there are foreign born. In Sweden 29.8 percent of doctors are

born abroad and 13.9 percent of the nurses.

There are no figures for Iceland in this OECD study

The differences are even bigger in the rest of the OECD. Less than

three percent of doctors in Poland and Turkey are born abroad, while 50

percent of doctors in Australia and New Zealand are. The number of

foreign born nurses in Poland and Slovakia is negligible, but in

Switzerland they make up 30 percent of the total.

The USA, Germany and the UK have the highest number of migrant

health care professionals. In the wake of the 2008 finance crisis

foreign health care professionals also moved from southern European

countries to Germany and the UK.

Brain drain

The countries loosing their newly educated health care professionals

face a problem at home. In 2010 the World Health Organisation

introduced a global code of conduct for the recruitment of health care

workers (Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of

Health Personnel, WHO, 2010). Meanwhile OECD countries have increased

their education of health care professionals, which has slowed the

immigration down to an extent. Certain countries, like Finland, Ireland

and Germany, have also entered into a cooperation on the training and

recruitment of health care personnel with countries of origin in order

to prevent problems arising.

Healthcare employment is generally less exposed to economic

fluctuations compared to other parts of the economy. The total number

of doctors and nurses has continued to increase in most OECD countries,

although the growth has slowed somewhat because of the crisis. Budget

cuts have also not affected health care professionals much in countries

which have been affected by the economic crisis. However, some

countries, like Greece, have decided not to allow the hiring of

temporary labour, and that only one in five people who retire will be

replaced.