A new Nordic report, ‘Youths in work in the Nordic region’, explores

the question in detail and looks at four different factors which might

explain the differences between the countries:

▪ The need for labour

▪ The structure of the education system

▪ The flexibility of workers’ rights

▪ Youths’ salary levels

Åsa Olli Segendorf, the report’s main author, concludes that

apprenticeships make a great difference to how many youths can be

classified as being employed. ILO’s statistics classify apprentices as

being employed, because they are being paid during their time in

training.

In Denmark nearly one in four employed youths is an apprentice, in

Iceland and Norway the figure is nearly ten percent while in Sweden the

number is negligible. Yet the differences in apprentice systems cannot

fully explain the different unemployment levels.

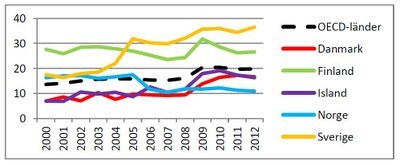

Media often quote numbers which show Sweden and Finland having the

highest level of youth unemployment. The difference is greatest among

the youngest age group; 15–19 year olds:

Unemployment 15-19 year olds. Source: AKU, OECD

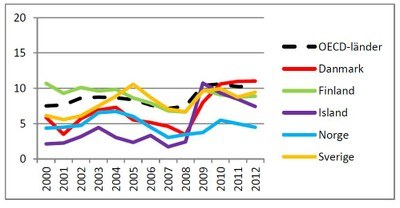

Yet comparing an older group of youths – 25–29 year olds – throws up

much lower unemployment figures. At the same time it is considerably

higher in Denmark, while Sweden and Finland’s figures are lower than

the OECD average. The 2008 economic crisis can be seen clearly in the

statistics for Denmark and Iceland. Norway still enjoys very low

unemployment:

Unemployment 25-29 year olds. Source: AKU, OECD

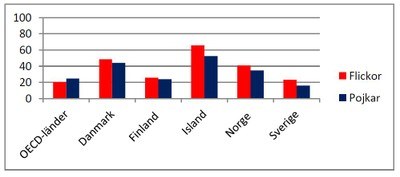

If you look at employment rather than unemployment, it is higher for

15–19 year olds in the Nordic countries compared to the rest of the

OECD. Another difference is the higher number of girls who work

compared to boys from that age group, which is not the case elsewhere

in the OECD:

Employment rate 15-19 year olds 2012. Source: AKU, OECD

Iceland stands out with a very high number of 15–19 year olds

working part time while studying.

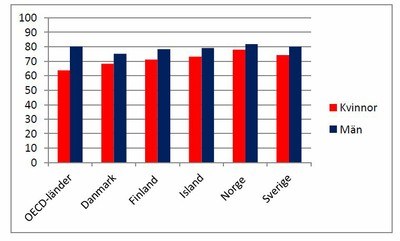

Looking at the older age group of 25–29 year olds, the differences

even out, while men work more than women:

Employment rate for 25–29 year old women and men, 2012

The report says Sweden has the least flexible workers’ rights for

young people. The wage distribution is also narrowest in

Sweden.

Young workers are at a disadvantage compared to middle aged workers

in the labour market because they have less experience and are

therefore often less productive.

“If you don’t compensate for the difference in productivity by

lowering starting salaries for young people, you might end up with a

higher relative youth unemployment because employers’ wage costs

increase,” writes Åsa Olli Segendorf.

It is nearly impossible to find statistics for the youths’ general

salary level, because the minimum wage – which is most often what young

people are being offered – is agreed on after negotiations between

employers and trade unions, rather than being introduced through

legislation like in most other European countries.

A 2011 Nordic survey of workers in the service and retail industry

does, however, throw up rather large differences between the countries,

especially for Iceland.

| Country | Minimum wage |

|---|---|

| Denmark | 18,946 |

| Finland | 15,888 |

| Iceland | 10,715 |

| Norway | 21,026 |

| Sweden | 17,325 |

Minimum wage in SEK after purchasing power parity

adjustment

The report does not give a final answer to why there are differences

in youth unemployment between the countries.

“But possible explanations include institutional differences in

education systems leading to different levels of labour market

attachment, differences in the flexibility of workers’ rights,

differences in minimum wages and the fact that the different countries

have different needs for labour,” writes Åsa Olli Segendorf.