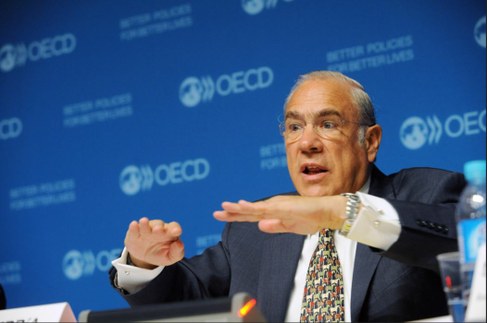

This was the message from the OECD’s Secretary-General Angel Gurría

when he presented the 2014 OECD Employment Outlook.

“While wage cuts have helped contain job losses and restore

competitiveness to countries with large deficits before the crisis,

further reductions may be counter-productive and neither create jobs

nor boost demand,” Angel Gurría told a Paris press conference on 3

September.

According to the OECD, unemployment in member countries will fall

somewhat in the next 18 months, from 7.4 percent in mid-2014 to 7.1

percent at the end of 2015. Nearly 45 million people are unemployed

within the OECD. That is 12.1 million more than before the financial

crisis hit in 2008.

No real wage growth

According to the Employment Outlook real wage growth has been nearly

stagnant since 2009, and in many countries — including Greece,

Portugal, Ireland and Spain — it has fallen by two to five percent a

year.

“Governments around the world, including the major emerging

economies, must focus on strengthening economic growth and the most

effective way is through structural reforms to enhance competition in

product and services markets. This will boost investment, productivity,

jobs, earnings and well-being,” said Angel Gurría.

This is partly a new message from the organisation which represents

34 of the world’s most industrialised nations. Gurría underlined that

countries with the largest budget deficits before the crisis were not

doing anything wrong by cutting costs and slowing wage growth.

“It has helped them restore competitiveness. But this might not be

the right remedy in the future.”

Although the situation is of course more difficult for those who

have become unemployed, the economic crisis has also hit those who

managed to keep their jobs.

“There is a lot of opposition to cuts in nominal wages. Instead we

have seen cuts to bonuses and overtime pay. But money is money, and

families’ purchasing power has suffered,” said Angel Gurría.

Minimum wage in 26 countries

Since prices have not fallen in line with wages, most people are

worse off. Increasing the minimum wage, like the USA and Germany have

done, at least helps those at the bottom of the salary pyramid. This

year’s employment outlook also features statistics on work quality.

Increased flexibility is no panacea either.

“Less than half of those in temporary jobs got permanent jobs three

years later,” Angel Gurría pointed out.

26 of the 34 member countries have now introduced a minimum wage — a

solution opposed by Nordic trade unions because they want to retain the

opportunity to influence wage negotiations. But the OECD also wants

minimum wages to be implemented in a manner which gives them maximum

effect. Regional differences should be taken into account, as well as

differences in age and skills.